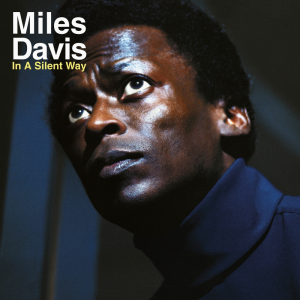

Writing anything about a figure like Miles Davis, and his music, is a task not taken lightly by anyone who appreciates jazz music, even just a little. The man clearly needs no introduction, and yet we sometimes struggle to understand what went on in his mind. So did he, this writer imagines.

In many ways, 1969’s In A Silent Way, and not the more well-known Bitches Brew of 1970, marked Davis’ entree into the world of jazz fusion. I say entree, but it was Davis along with Larry Coryell and Charles Lloyd who pioneered the genre, and as such, In A Silent Way is one of the first jazz fusion albums. So what is it that makes fusion, fusion? Any jazz scholar will scoff at such a question, but it does deserve some thought. The first, most obvious departure from Davis’ previous work is the instrumentation. The electric guitar (John McLaughlin) and electric pianos (Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea…feeling the power yet?) were new additions to the lineup for Miles, and jazz as a whole.

The format of this particular album was different, as well. In A Silent Way was the first album to be cut and spliced by Miles’ longtime producer Teo Macero, and Macero followed the classical sonata format (exposition–development–recapitulation), a departure from the incumbent styles of jazz, hard bop and free jazz of the 1960s. This format is used in both tracks/sides of the album. Miles’ use of repetition and droning rhythm section parts can be traced back to John Coltrane’s 1965 A Love Supreme, and from there back to Ravi Shankar and India, both of which influenced Coltrane enough for him to name a son after the sitar player. This combination of new musical instrumentation, format, and Eastern influence allowed Miles to begin his pursuit of “the best damn rock ‘n’ roll band of all time” which would groove hardest on Davis’ 1971 A Tribute to Jack Johnson.

“All-star” would be quite the understatement in describing Miles’ personnel choices for In A Silent Way. On soprano saxophone is the ever-present Wayne Shorter, who became famous while writing and playing for Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, and moving on after a decade with Miles to form Weather Report with Joe Zawinul, who played organ on this album and co-wrote side two. On electric guitar we find John McLaughlin, who was in the middle of an extremely busy two years: the previous month he’d recorded his debut album, Extrapolation; he’d just moved to New York from England to play in Tony Williams’ (yep, he played drums on this album, too) Lifetime trio with Larry Young; he’d soon befriend Billy Cobham and form one of the greatest fusion groups of all time, the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Sitting behind dual electric pianos are Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea, two jazz titans who would go on to lead extremely successful groups of their own. On bass is Dave Holland, whom Miles had picked up at London’s Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club the year before, and who was in the middle of an extraordinary first two years in the big time. It’s often said that in jazz, especially jazz fusion, all roads lead to Miles Davis. Perhaps you can see why.

Side 1 is “Shhh/Peaceful.” The exposition/recapitulation, “Shhh,” features a droning D major in the bass and an even more repetitive line of sixteenth notes in the hi-hat, setting the stage for a musical experience that compels the listener to look within for meaning to the music, rather than from without (save that for side 2). Every time I listen to Shhh/Peaceful, I come out on the other side unsure of how much time has passed (although I know it’s about 18 minutes), wondering why I didn’t choose to loop the track for as long as I can meditate. Inevitably, the listener will fall into a deep introspection during this track, as the stellar musicians continue their song into the distance. Wikipedia’s categorization of this album into both “jazz fusion” and “space music” is apt. Not to mention the name of the track.

Side 2, “In A Silent Way/It’s About That Time” starts off much more peaceful than even “Shhh,” opening with a pastoral open A chord from McLaughlin, a chord that gives the listener a sense of peace, and yet a suspicion of much energy to come. The calm before the storm, perhaps. “It’s About That Time,” the development section, is all about that groove. You know the one. It’s been stuck in my head for years now. Atop this simple yet infectious groove (we have Chick, Tony, and Dave to thank for that) sit two of the finest solos in all of Miles’ catalogue, plucked from some of the finest improvisers in jazz, McLaughlin, and Shorter. After a solo from Miles, “In A Silent Way” recapitulates, bringing the listener back to his senses.

Many critics have written many words about Miles Davis’ first fusion album, but Rolling Stone’s Lester Bangs might have written it best: it was “the kind of album that gives you faith in the future of music. It is not rock and roll, but it’s nothing stereotyped as jazz either. All at once, it owes almost as much to the techniques developed by rock improvisers in the last four years as to Davis’ jazz background. It is part of a transcendental new music which flushes categories away and, while using musical devices from all styles and cultures, is defined mainly by its deep emotion and unaffected originality.”